What links the intelligence and the Saski Palace?

General Staff

The rebirth of the independent Polish state in 1918 was a complex process, requiring, among others, the establishment of an administrative system – both civilian and military. Measures in this direction were already taken in the final months of World War I. On the memorable 11 November 1918, the Regency Council transferred military supremacy and supreme command of the Polish Army to Józef Piłsudski; several days later also the civil authority was handed over. Piłsudski held this function until the promulgation of a decree on the supreme representative authority of the Republic of Poland.

At the beginning of the emerging statehood, the Second Polish Republic had to wage the Polish-Bolshevik war and defend its eastern borders. One of the main military bodies of the state was the General Staff of the Polish Army, which had its headquarters in the Saski Palace. The first Chief of Staff was Lt. Gen. Tadeusz Rozwadowski. Between 1922 and 1923, this position was also held by Marshal Józef Piłsudski – at that time, he occupied an official apartment on the second floor of the southern wing, overlooking the Saxon Garden.

In 1928, the General Staff of the Polish Army transformed into the Main Staff (Sztab Główny).

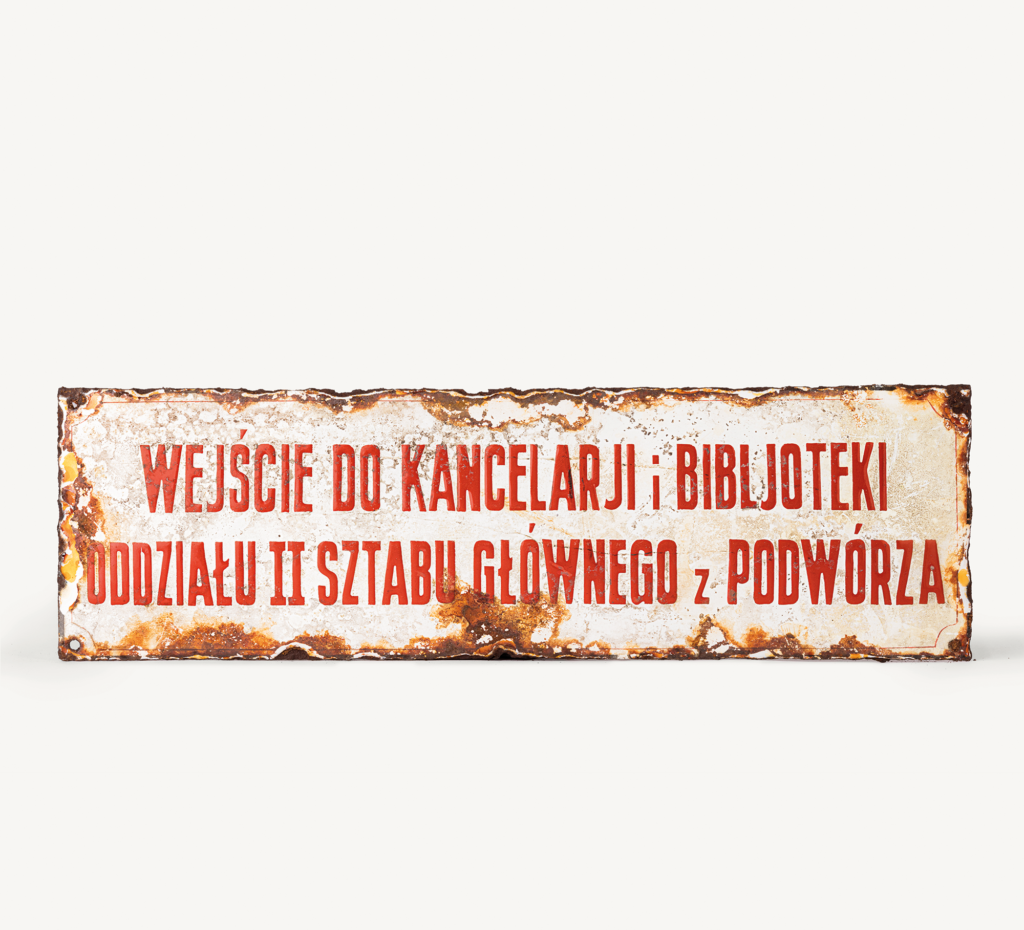

Intelligence in the Saski Palace

The traditions of cryptological success in the Saski Palace date back to the Polish–Bolshevik War. In August 1919, Captain Jan Kowalewski broke the first Soviet cipher, beginning by... breaking off a few teeth of a comb. The team he later led deciphered over one hundred enemy messages, contributing to the victory of the Polish Army over the Red Army in the Battle of Warsaw.

Another historic event took place more than a decade later. In September 1932, young mathematicians who had taken a secret cryptology course in Poznań were recruited to the Cipher Bureau of Section II of the General Staff of the Polish Army. Back in December, in one of the secret rooms of the Saski Palace, Marian Rejewski broke the cipher of the German Enigma machine for the first time. In the following years, he worked together with Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski on decrypting the ever-changing Enigma code, using modern and effective tools such as the cyclometer, Zygalski’s sheets and Rejewski’s bomb. The team also commissioned the AVA Radio Company to build replicas of the machine. Some of these Enigma duplicates were handed over to the French and British intelligence services just before the outbreak of World War II.

Enigma

What is Enigma? The word itself comes from Modern Greek and means a mystery, a riddle. The name perfectly describes the German cipher machine based on the principle of rotating rotors. Constructed after World War I by Arthur Scherbius, the Enigma cipher was for years considered unbreakable. What was the catch? The machine used a new encryption method, where the key was its proper configuration. The rotors, rings and plugboard had to be selected and set, and an individual key had to be entered each time. In the Enigma, which resembled a typewriter, pressing the key with the letter A could, for example, correspond to the target letter H, and when pressed again – a completely different one, such as Z. This resulted from the constant rotation of the rotors, meaning the number of possible combinations was unimaginably large.

The Cipher Bureau picked up the gauntlet. To meet the challenge, it engaged mathematicians. In 1929, a secret course for students was organized at the University of Poznań, from among whom three future conquerors of Enigma were selected: Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski.