FRAGMENTS OF THE PAST

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

What has the Saski Palace been throughout history?

In the many years of its history, the palace served various functions It was a seat of aristocratic families, a royal residence, and a witness to the tumultous events of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.

Over the centuries, the building had many owners and changes in appearance. It began as a Baroque palace, funded by the poet Jan Andrzej Morsztyn. During the reign of the kings of the Saxon Wettin dynasty: Augustus II and his son Augustus III, the palace – later called the Saski Palace – was a private royal residence. After losing its status of a royal residence, it became home to such institutions as the Warsaw Lyceum and the Merchants’ Exchange, but over time the building began to fall into disrepair. At the end of the first half of the 19th century, it was completely rebuilt.

After Poland regained its independence in 1918, the building remained in the hands of the Polish Army. The top-secret Cipher Bureau was located here.

The place took on a new meaning in 1925, when the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was established in the arcades of the Saski Palace colonnade.

The palace was blown up in December 1944 by the occupying German army and was not rebuilt after the war.

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

Why did Warsaw become the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth?

The act of the Union of Lublin in 1569 between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which led to the creation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, is considered a historic moment for Warsaw. As Warsaw is located much closer to Vilnius than Kraków (the seat of Polish kings), it was therefore chosen as the seat of the Polish Parliament – the Sejm.

Previously a town serving as a local center of an agricultural area, Warsaw slowly began to take on broader civic functions. It was here that the Sejm debated, elections were held and kings were elected. Goods and people streamed into the town.

The times of the Saxon rule strengthened the position of the city and contributed to its further development. To this day, the fastest land route from Dresden to Vilnius runs through Warsaw.

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

What kind of a city was the 17th century Warsaw?

The transfer of the royal residence of Sigismund III Vasa from Kraków to Warsaw resulted in a rapid development of the city which could be perceived as a new capital – representatives of the nobility, magnates with their courts, as well as numerous merchants and craftsmen began to flood Warsaw.

Warsaw grew rapidly, its expansion fueled by the inclusion of new areas used for the construction of opulent magnate mansions.

In the second half of the 17th century, the development of Warsaw slowed down due to the destruction caused by the war known in Poland as the Swedish Deluge.

After the Swedish invasion, the land formerly belonging to the head of the territorial administration was parceled out in order to repopulate the lands harmed in the war. In 1661, the poet Jan Andrzej Morsztyn was given one of the plots of land by King Jan Kazimierz. He built a Baroque palace, which later became the Saski Palace.

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

What kind of place was the Saski Palace during the reign of the Wettin dynasty?

The palace, as a royal, representative space, held a unique place on the map of Warsaw.

The royal family, along with its court, periodically stayed in the palace. At those times, the place was bustling with life, audiences were held for guests and diplomats and a variety of entertainment was provided.

At the heart of the Saski Palace was the great ballroom which stretched across the entire width of the building on the first floor and overlooked the park. Its walls were decorated with red-and- gold cordovan – a type of painted, embossed and gilded leather wallpaper. Festive receptions, concerts and dances were organized in the ballroom. In 1730, the hall was equipped with an illumination system, while the mirrors hanging on the walls made the space seem even larger.

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

How was Saxon Axis (Oś Saska) established?

The idea of a new urban layout for Warsaw which we now call the Saxon Axis is accredited to King Augustus II. The “entre cour et jardin” (“between courtyard and garden”) arrangement was modeled – like many other urban systems of that era – on the French Versailles.

The designation of a new axis leading from the river to the city, from east to west, perpendicular to the Royal Route, was a revolutionary change.

Bringing focus to this part of Warsaw had a symbolic dimension: it displayed the agency of the king and his administration as well as set a new direction for the political and cultural life of the country.

This innovative concept gave Warsaw a new, functional form. It also closed a stage in the development of the capital hidden behind the city walls.

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

How did the Saxon Axis urban layout change Warsaw?

The axis gave the city layout an innovative, bold direction. New military and commercial facilities along with the most important residences were to be built there.

In 1727, the Saski Garden was opened to the inhabitants of Warsaw as the first public city park in the Commonwealth and one of the first in Europe. The palace courtyard was also made available to the public. When the palace lost its residential function, it became a city square.

The vestiges of the Saxon Axis are still visible in the urban space of Warsaw. It leads from the Royal Route through the Saxon Garden towards Mirów market halls. The former courtyard is today’s Marshal Józef Piłsudski Square, a place for festivities and state events. The Saski Garden remains one of the favorite places for walks of Warsaw residents and their guests.

Warsaw Rising Museum

Who lived in Warsaw in the 18th and 19th century?

For centuries the number of people coming to the Polish- Lithuanian Commonwealth exceeded the number of those who left. The Commonwealth accepted immigrants from German- speaking countries, France, Italy, England, Turkey and Russia.

People who came to Poland believed that a better life awaited them on the banks of the Vistula River. One of them was Nicolas Chopin, who initially worked in Poland as a modest accountant. He was also a tutor for the Skarbek family in Żelazowa Wola, where he met his future wife – a Polish noblewoman Tekla Justyna Krzyżanowska. In the fall of 1810, Nicolas took the position of a French language teacher at the Warsaw Lyceum (a secondary school) located in the Saski Palace. Until 1817, the Chopins, together with their children: Ludwika, Fryderyk, Izabela and Emilia, lived in an apartment on the second floor of the northern wing of the palace.

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

What social changes took place in Warsaw at the end of the 18th century?

At the end of the 18th century, all eyes were on Warsaw. The Parliament (Sejm Wielki) debating in the capital was to secure sovereignty of the state. The social force backing the implementation of these reforms was to be the bourgeoisie.

The Law on Cities (Prawo o miastach), enacted in 1791 and incorporated into the Constitution of 3 May 1791, became a symbol of the alliance between the nobility and the bourgeoisie. The act created a path for the free people, craftsmen and foreigners to join the ranks of the bourgeoisie. The townspeople themself could now become members of the nobility by purchasing land or with state and military service.

These changes, together with the guarantees of personal freedoms for the bourgeoisie included in the Constitution, heralded the loss of control of local oligarchs and magnates over the process of social advancement of the inhabitants of the Commonwealth.

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

What were typical professions of the 18th century Warsaw residents?

Rapid development of Warsaw attracted people from both within the country and from abroad. The aristocracy, wealthy nobility and all those who saw a chance for a better life on the Vistula River flooded the city.

During the long reign of the Saxon Wettin dynasty, many artists, merchants and craftsmen came to Warsaw, encouraged by the possibility of gaining quick wealth.

The most numerous group in the occupational structure of the population were craftsmen who satisfied the everyday needs of the inhabitants. Artisans, who worked only for a small clientele, were fewer in number at that time. Additionally, many people were engaged in trade.

The residential nature of the city resulted in a high demand for all kinds of domestic help. In the second half of the 18th century, the local press ran its first job advertisements for prospective employees.

Warsaw Rising Museum

What artifacts were left behind by the 18th century Varsovians?

A significant part of the 18th century items unearthed during archaeological excavations come from... garbage heaps. Paradoxically, these artifacts were saved only because their owners once tried to get rid of them.

On the northern outskirts of the Saski Palace excavation area there were two large garbage pits built at the end of the 18th century in place of former latrines. Most of the archaeological discoveries found in the area were objects of everyday use.

The scientists working at the excavations were surprised by the large number of bovine ribs with cut out discs which transpired to be production waste from a button workshop. Finished goods and other artifacts were also found in the garbage pits which helps us imagine everyday life in those times.

What was the most valuable find?

One of the most valuable items found during the excavations at the Saski Palace is a ring with four diamonds. Made of silver and gold, it lay for many years at the bottom of a 19th century latrine. Imagine the surprise of the archaeologists who found such a valuable object!

This piece of jewelry could be a family heirloom or an engagement ring – it was believed that diamonds, as the most durable of the stones, made relationships eternal. Most likely, this precious item slipped from the finger of one of the ladies using a secluded privy. Or was it thrown away deliberately?

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

Which parts of the world did the items found in the basements of the Saski Palace come from?

During the excavations, the archaeologists came across many unique items from all over the world. The resulting collection includes fragments of faience vessels from English manufacturer Wedgwood, as well as those produced in Delft in the Netherlands. Wall tiles and fragments of pipes are also of Dutch provenance.

As King Augustus II was famous for his love of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, the palace used tableware imported from China. Its fragments were also found during excavation works.

Well-preserved stoneware bottles for mineral water with the inscription “SELTERS” were also discovered in the palace garbage heaps. Selters water, coming from the springs located in the Westerwald region in Germany, was supposed to help with various ailments. It is worth remembering that fresh water only started flowing through the Warsaw waterworks at the end of the 19th century.

Was the 18th century a time of changes and progress for Warsaw?

The 18th century was a time of great experiments, developments in science, education, trade and administration as well as a time of building modern armies.

Sons of nobility began to leave their hometowns to look for a better life in Warsaw. Their arrival in the city meant that distant classes of burghers and noblemen began to intermingle and the number of marriages between representatives of different classes increased.

This development gave rise to the phenomenon of elite convergence. These changes could not have taken place without the unique atmosphere of the capital city, conductive to change and progress.

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

What cultural events took place in the Saski Palace?

Cultural life flourished in the Saski Palace: concerts, performances and social gatherings were organized. The Wettins were patrons and collectors of art.

The reign of Augustus II was an era of thriving court theater scene, as several theater halls were built or restored in Warsaw. In 1724, a theater was established in the Saski Palace itself – in a building added to its northern wing. The king brought in both Italian commedia dell’arte groups as well as French drama troupes.

His son, King Augustus III, opened the theater stage in the Saski Garden, the so-called “Operalnia”, to the general public. It was the first free-standing theater building in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

What was eaten in the Saski Palace?

In the Saxon times, a new, French way of setting and decorating the table became fashionable. Game or poultry was served on the largest dishes, while medium-sized tableware was used for soups, fish, meat, as well as tarts and pates. The smallest vessels held numerous side-dishes.

In addition to traditional dishes such as broth, borscht, boiled beef, bigos (stewed cabbage with meats) or goose, products imported from abroad were also served, such as capers, olives, anchovies, potatoes and marinated oysters. Numerous finds of oyster shells at the excavation site prove that they were very popular at the royal table. Among the remains found in the garbage pits were duck, boar and sturgeon bones, as well as the remains of a turtle, which was then considered a fish. Desserts and sugars prepared by Warsaw confectioners were the grand finale of every meal.

What did the inhabitants of Saski Palace drink?

In the 18th century, vodka, wine and beer were very popular and used in modest doses to “improve digestion”. The tendency to consume stronger drinks was confirmed by archaeological finds. Numerous bottles, a demijohn and glass fragments were discovered in the palace cellars. An interesting find is a glass with the “AR3” (Augustus Rex 3 – King Augustus III) monogram. The king enjoyed wine, although he did not drink much of it. After a hearty dinner, he usually smoked tobacco and drank Saxon beer.

Coffee, chocolate and tea were also in vogue. Until the end of the 18th century, these beverages were served with breakfast. Dainty cups were used to consume tea which was a luxury at that time.

What happened in Warsaw after the Constitution of 3 May 1791 was passed?

The Constitution prepared by the king and a broad coalition of reformers was supposed to modernize the political system of the Commonwealth. However, the great landowners could not afford to lose their power and incomes. The resulting betrayal of a handful of magnates became a pretext for Russian intervention.

A war broke out in defense of The Constitution of 3 May 1791, as the neighboring countries did not want to see the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth a strong and competitive state.

However, the king surrendered his army before the Russians reached Warsaw. Two years later, in 1794, citizens of the Commonwealth participating in the Kościuszko Uprising showed their patriotism and bravery. Jan Kiliński – a craftsman and a burgher – became a symbol of the resisting capital. Fierce fights took place in the courtyard of the Saski Palace. Only the brutal Massacre of Praga district broke the spirit of the residents of Warsaw.

What do we know about the role of the palace during the Kościuszko Uprising?

During the Kościuszko Uprising, on the 17th of April, 1794, a bloody skirmish took place in the courtyard in front of the Saski Palace. The people of Warsaw repelled the strike of a column of Russian troops aiding the besieged tsarist general Iosif Igelström, cornered by insurgents on Miodowa Street. The Polish unit, headed by Captain Drozdowski, fired its cannon and retreated, stopping in the courtyard of the neighboring Brühl Palace.

The Russian troops under the command of General Ivan Novitskiy, who at some point lost control of his soldiers, were under constant fire. When the Russians scattered, they broke into the unprotected Saski Palace and nearby tenement houses, stealing furniture, valuables and alcohol stored in the cellars.

When a unit of Poles from the 10th Regiment appeared on Królewska Street, the Russians panicked, headed towards Aleje Jerozolimskie and fled the city.

How was the history of the palace marked by the tragic experience of the Partitions period?

As a state, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth required thorough reforms. The Constitution of May 3 1791 was supposed to revitalize its agency.

The partitions (occupation by Russia, Prussia and Austria) stopped these efforts. The lands of the Commonwealth were divided regardless of the cultural, economic and family ties built over the centuries. Each of the partitioning states pursued a policy of integrating its territories with its own empire.

In 1797, the Saski Palace was bought by the Prussian government, which then rented its premises. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Warsaw Lyceum (a secondary school) was located here. After the Congress of Vienna, the palace became the property of the government of the Kingdom of Poland, and after the January Uprising it was handed over to the municipal administration and rebuilt. In the 1860s, the building was taken over by the management of the Warsaw Military District. The Russians stayed here until their evacuation from the city in August 1915.

How did the role of Warsaw change in the 19th century?

During the partitions, Warsaw lost much of its importance, but was still the capital of the Kingdom of Poland and benefited from its central location at the intersection of crucial trade routes. In the Russian Empire, it was the third largest city, right after Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Development processes could not be stopped entirely. Warsaw was still a center of political, economic and cultural events, even though it was subjected to hostile behavior of the partitioning authorities, aimed at reducing it to a provincial town.

What mark left the tsarist authorities on this place?

In the times of the Kingdom of Poland, both the square and the Saski Palace reflected the tragic fate of Poland. The representative nature of the palace meant that the partitioning authorities chose its former courtyard to erect symbols of their domination. In 1841, the Russian authorities placed in the square an obelisk commemorating the seven loyalist Polish officers who refused to join the November Uprising.

At the end of the 19th century, the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral was erected in the square – a grandiose symbol of Russian domination towering over the central and representative part of the city.

A huge, free-standing 73-meter bell tower flanked the cathedral - one of the tallest buildings in Warsaw at the turn of the century. Both buildings dominated over everything in the vicinity, completely changing the character of Saski Square.

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

Why was the original palace rebuilt?

The rebuilding of the palace was already considered at the end of the 18th century.

The Baroque palace was significantly damaged during the Kościuszko Uprising and the November Uprising brought further destruction.

The design of the reconstruction of the Saski Palace itself was selected through a plebiscite, which can be compared to architectural competitions of today. The remodeling was to be conducted under the condition of creating a passage between the square and the Saski Garden. The investor, a merchant from Brest-Litovsk called Jan Skwarcow, was obligated to implement these municipal guidelines.

This is how the familiar form of the Saski Palace was created. Reconstruction was completed in 1842. It made history as the work of Adam Idźkowski, although many elements came from the design of Wacław Ritschel. The neoclassical building quickly became a part of the city skyline.

What famous figures were associated with the palace?

Many extraordinary people lived and worked in the palace.

Military commander Jan Sobieski, who would later become King of Poland, frequented the place.

For several dozen years, the palace was the seat of Polish kings – Augustus II and his son, Augustus III.

In the 19th century the palace was a venue for concerts, balls and exhibitions.

Fryderyk Chopin spent several years of his childhood and started learning to play the piano in the Saski Palace – it was here that he wrote his first pieces. Writer Józef Ignacy Kraszewski visited the place. The young poet and writer Jadwiga Łuszczewska, called “Deotyma”, lived with her family in the Saski Palace and her parents held here one of the most famous literary and artistic salons in Warsaw.

In the years 1922-1923, Marshal Józef Piłsudski lived in the palace. It was here that the specialists from the Cipher Bureau worked out the famous German Enigma in the early 1930s.

Mead bottle made of greenish glass, with relief inscription “+BENEDECTINE+”,

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

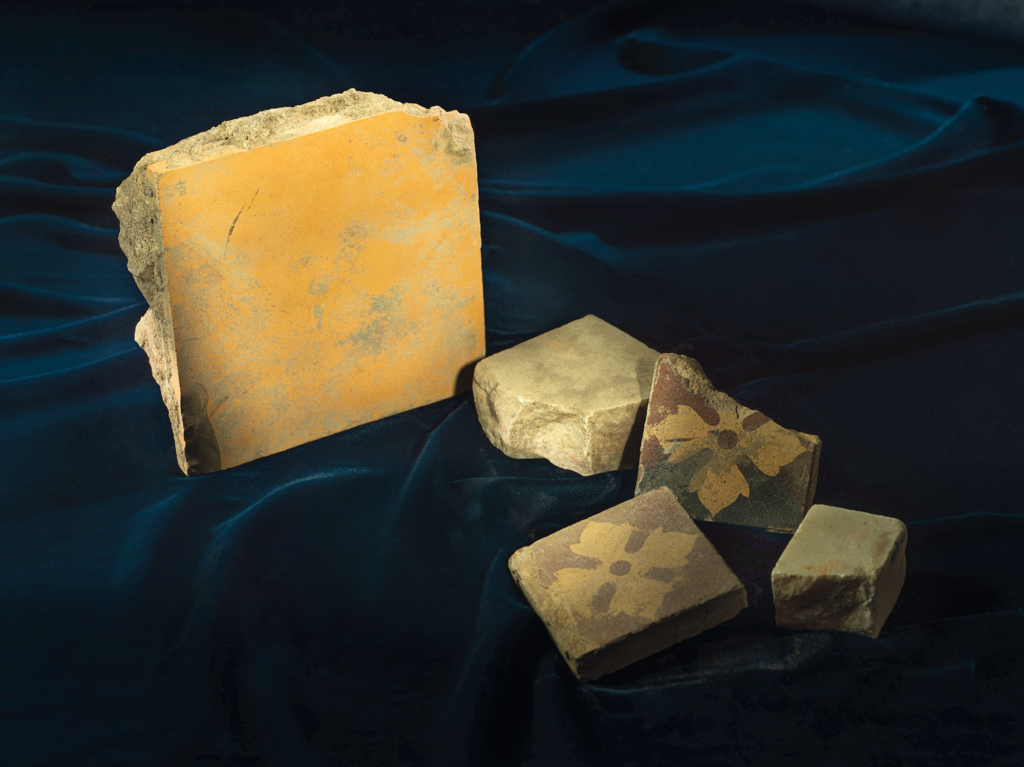

What relics of the past were found on site of the former Saski Palace?

Remains of both Baroque and Classicist buildings were found within the preserved cellars. Fragments of window frames, cornices and fireplaces made of sandstone reused during the reconstruction by the 19th century builders were uncovered. In the area of the former royal garden, located in one of the inner courtyards of the palace, elements of damaged Baroque sculptures were discovered.

Deep traces of plow use have survived to our times, proving that the area of today’s Marshal Józef Piłsudski Square was once covered by arable land. A well which used to be located on the premises of the farm belonging to the local official was also discovered.

Archaeological excavations revealed the remains of fortifications from the Vasa period, a fragment of the road leading to the Grzybów neighborhood and the relics of the wooden court of the Lublin castellan, Andrzej Firlej, destroyed during the Swedish invasion.

What did the year 1918 and the regaining of independence mean for Warsaw?

The Great War waged by the partitioning powers left the Polish lands in ruins. Warsaw suffered the greatest losses during the retreat of the Russian army in 1915. Entire industrial plants, museum collections and universities were evacuated deep into Russia, along with their crews and specialists.

Independent Poland had to rise from its ruins and face the challenge of unifying social and economic systems of the three partitions and regions which had been integrated with three different empires for over a hundred years.

This is how independence began. Warsaw once again became the capital of free Poland, rising to meet new expectations. It would not have been possible if it were not for another great wave of migration to the capital.

archaeological site Warsaw, Saski Palace. Museum of Warsaw

What was the life of the inhabitants of Warsaw like after regaining independence?

Warsaw was experiencing rapid development in all spheres of life. The fast pace of both planned and spontaneous changes meant that chaos clashed with order in the capital at any given time. Ugliness met beauty, noble gestures occurred at the same time with acts of lawlessness.

The difficult process of rebuilding Polish statehood after more than a hundred years of partitions was completed thanks to the strength and determination of the inhabitants of the capital and the whole country.

What does the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier symbolize?

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is a symbol of the heroic struggle for the homeland and its independent existence. In 1925, it was incorporated into the monumental colonnade of the Saski Palace, becoming one of the most important symbols of Warsaw.

Here, in the central place of the capital of the Republic of Poland, the flame of memory of the sacrifice suffered by all those who died in the fight for freedom and independence was burning.

How did the role of the Saski Palace change after regaining independence?

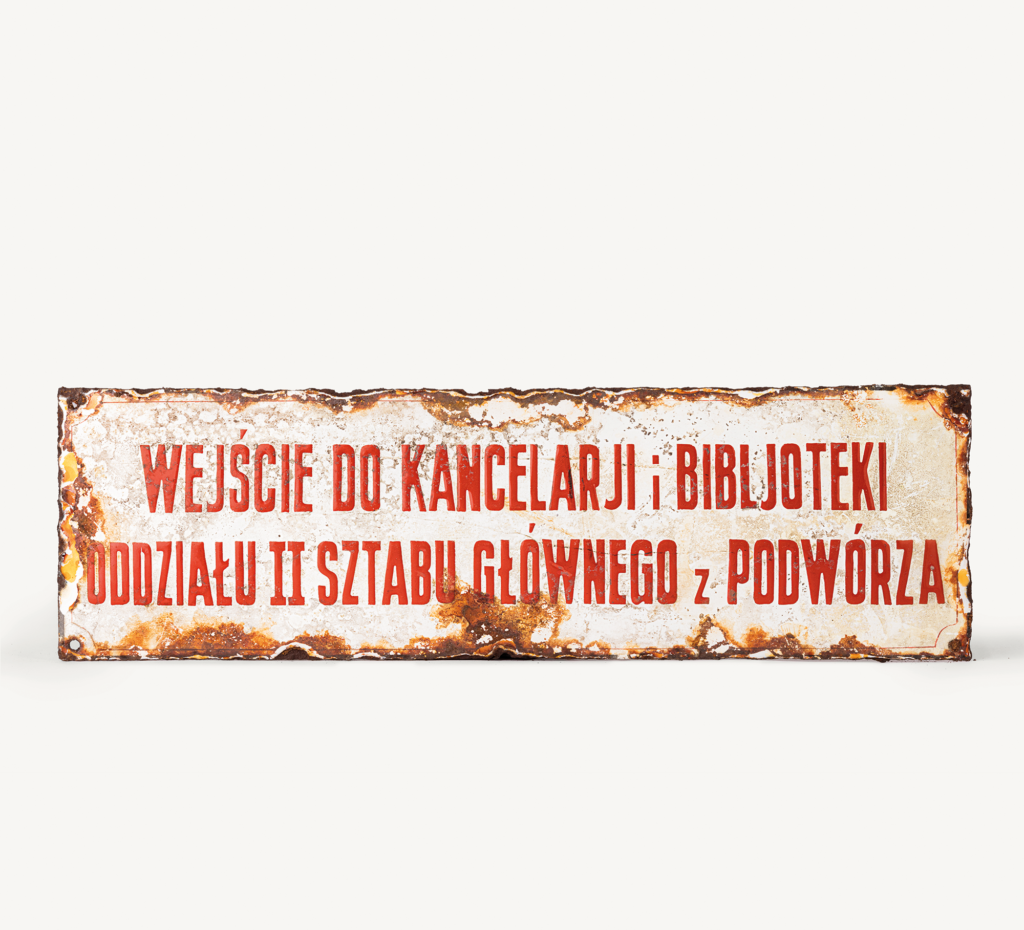

With Poland regaining independence in 1918, the Saski Palace became the seat of the General Staff of the Polish Army.

The northern wing of the building housed the Cipher Section of the II Division. This cell, headed by Lieutenant Jan Kowalewski, broke the codes of the Red Army, contributing to the defeat of the Bolshevik troops near Warsaw in 1920 and the final victory in the Polish-Soviet War.

For several months, Marshal Józef Piłsudski lived in the Saski Palace with his family in the apartment designated for the Chief of Staff. In the 1930s, cryptologists Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski worked in the building. At the end of 1932, thanks to their vast knowledge and persistence, they broke the code of the German encryption machine Enigma.

On September 1, 1939, the Main Staff was transformed into the Staff of the Supreme Commander.

What was the function of the Marshal Józef Piłsudski Square in interwar Warsaw?

In the interwar period, many secular and religious events, as well as the most important state ceremonies were held in Saski Square, which was renamed Marshal Józef Piłsudski Square in 1928. It was also a popular spot for military parades. On May 3, 1923, a monument to Prince Józef Poniatowski was unveiled in front of the Saski Palace.

City residents flocked to this space and gathered in the surrounding cafés and restaurants, especially near the Europejski Hotel. One of the many unforgettable events in the square was the performance of Jan Kiepura, who sang in this place during the celebration of the Days of the Sea in June 1936.

The square, which was teeming with life in the interwar period, was one of the top hotspots of Warsaw.

“entry to the office and library division ii of the general staff from the back”, Warsaw Rising Museum

What did World War II mean to Warsaw?

On September 1, 1939, another era of prosperity ended for Warsaw.

In 1940, the German occupying forces developed the Pabst Plan: an urban plan for Warsaw. According to its outlines, the majority of Warsaw was supposed to be torn down, its population limited to one hundred thousand, i.e. reduced more than tenfold.

All the Jews living in Warsaw – one third of Warsaw’s inhabitants – were sentenced by the Germans to extermination. Between 1940 and 1942, about 100,000 people died in the newly formed ghetto, while another 300,000 were murdered in the Treblinka extermination camp. After the fall of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, all the buildings in the area – about 12% of the city – were destroyed.

According to various estimates, between 150,000 and 200,000 Varsovians lost their lives during the Warsaw Uprising and 25% of the city was destroyed.

After the ceasefire, the planned and systematic destruction of Warsaw and the displacement of its population continued.

At that time, priceless objects of Polish heritage were burned and demolished, such as collections of the National Library, the Royal Castle, or the buildings of the Old Town. The Palace on the Isle and Belweder were burned down. It was then that the Saski and Brühl Palaces disappeared from the face of the earth.

How did the function of the square change during the German occupation of Warsaw?

During the occupation, the square became the center of the German government district. The Saski Palace was the seat of the city’s military commander, and the neighboring Brühl Palace was the seat of the governor of the Warsaw district, Ludwig Fischer. Jews were forbidden from entering the square.

Germans changed the name of the square twice – in May 1940 it was renamed to Sachsenplatz, and six months later to Adolf-Hitler-Platz.

The occupying forces also perceived the square as a representative space, as they organized various celebrations and parades. During Warsaw Uprising, the tanks used against the insurgent barricades stationed by the palace.

wound on a wooden grenade shaft, Warsaw Rising Museum

Why did the Germans mine and blow up the Saski Palace?

After the fall of the Warsaw Uprising, the Germans began to systematically destroy Warsaw. They burned down the remaining tenement houses and blew up the more valuable buildings. They deliberately and systematically annihilated cultural properties and objects valuable to Polish national identity.

Polish archivists, librarians and museum workers, led by the director of the National Museum Stanisław Lorentz, carried out the operation of securing and removing some of the undamaged collections from the city.

In December 1944, the Saski and Brühl Palaces were looted, plundered and then blown up by the Germans. Mining the Saski Palace took several days, the process of blowing up lasted from 27 to 29 December.

The only thing that remained of the Saski Palace was the central fragment of the colonnade with the ruins of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, which was rebuilt in a rudimentary form in early 1946.

Why wasn’t this part of Warsaw rebuilt right after the war?

Many architects and restorers drew attention to the need to rebuild the Saski and Brühl Palaces. Attempts were made to stop the removal of debris until a thorough research and documentation of the rubble could be completed. Unfortunately, to no avail.

The surviving walls of the buildings were demolished and the area was evened out. The rubble, along with many fragments of the buildings that could still be used for reconstruction, was taken to the opposite bank of the Vistula River and deposited in a place where Stadion Dziesięciolecia (10th-Anniversary Stadium) was later built. In 2011, the facility was rebuilt and became the National Stadium.

The reconstruction of the palace, planned from 1946, never went beyond the phase of projects concerning the development of the then Victory Square. The reasons were not only financial, but also political.

The idea of bringing this important building, a symbol of Polish national identity, to life, didn’t suit the authorities of the Polish People’s Republic (Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa).